Universities were divided into five types: 1) traditional elite (long-established, research-intensive universities); 2) red brick (established in major cities in the nineteenth and early twentieth century to serve the needs of industry and science); (3) 1960s campus university (also known as ‘plate glass’ universities, established in the wake of the 1963 Robbins report recommending university expansion); (4) post-1992 or ‘new’ universities (mostly former polytechnics, known as ‘post 1992 universities’ because they were granted university status in 1992, originally focusing more on vocational training but now offering a wide range of courses); and (5) ‘Cathedrals Group’ (the name given to a group of 16 universities established as teacher training colleges by the Anglican, Roman Catholic and Methodist churches, mostly in the nineteenth century, which, like the post-1992 universities, now offer a wider range of subjects).

Differences in spread of chaplains across universities

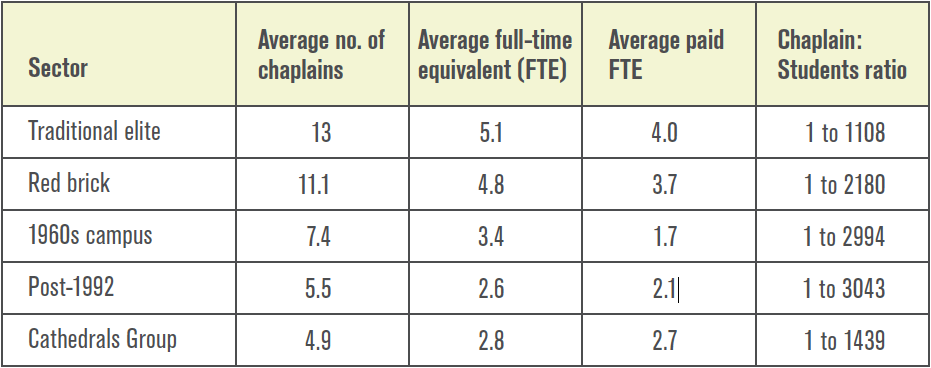

Chaplaincy provision differs across the university sub-sectors. A 2017 web search of chaplaincy websites revealed that the older the university sector, the more chaplains there were. The traditional elites had the most chaplains (an average of 13), then the red brick universities (11.1), the 1960s campus universities (7.4), the post-1992 universities (5.5), then the Cathedrals Group (4.9). But this does not take into account the different sizes of the institutions. When the number of chaplains is compared to the number of students enrolled, the picture changes. The best chaplain to student ratio remains in the traditional elites, but the Cathedrals Group is in second place, followed by red bricks, then the 1960s campus universities, with chaplain numbers proportionally lowest at post-1992 universities.

Differences in remuneration

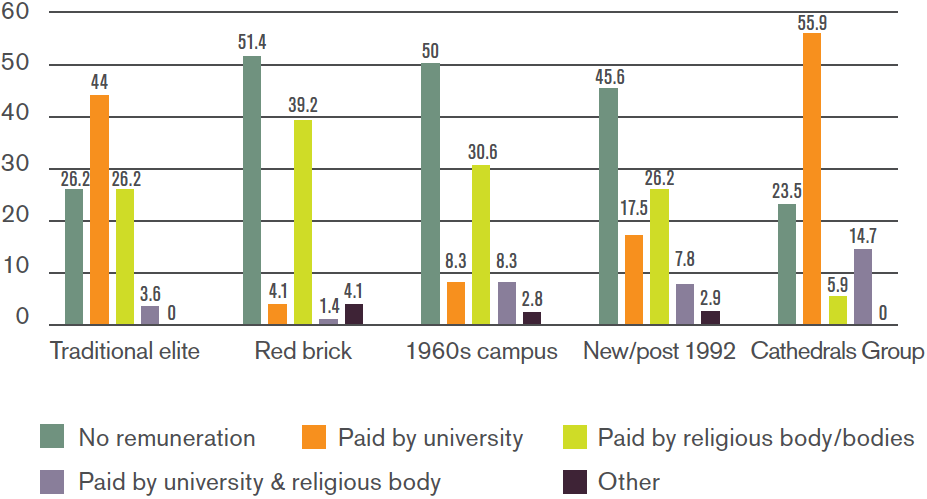

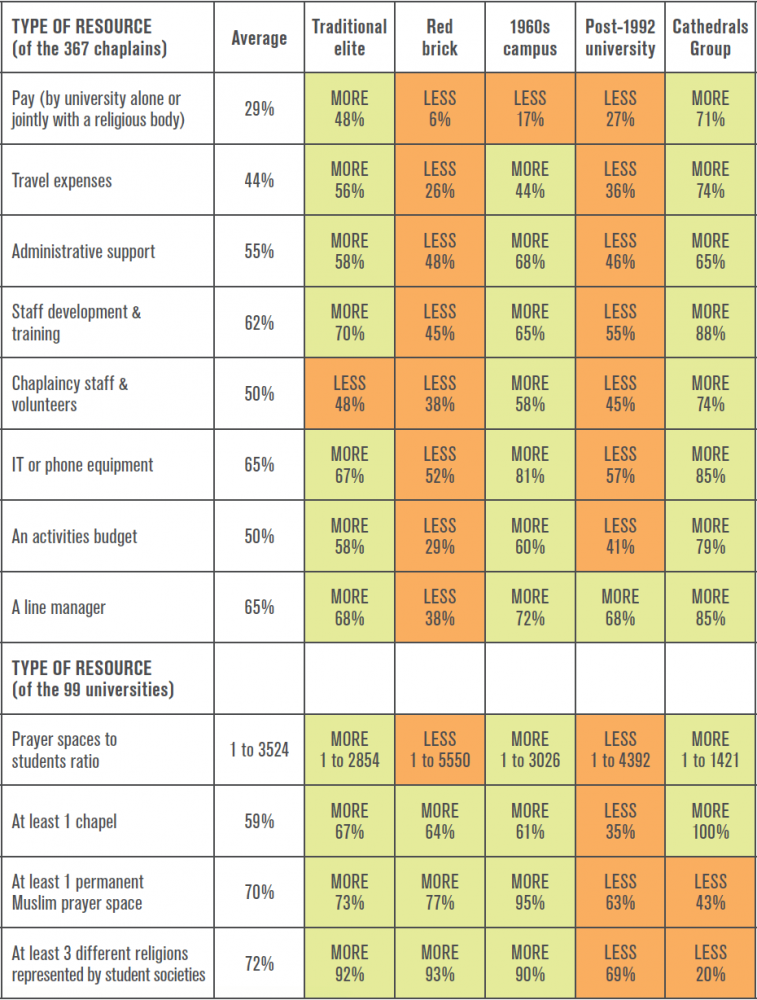

There are large differences in whether chaplains are paid and by whom, by type of university, as Figure 6 shows.

Among the traditional elite universities and the Cathedrals Group, payment by the university is most common, with figures highest for the Cathedrals Group, where there is also the lowest ‘no remuneration’ figure. Cathedrals Group institutions therefore invest the most financially in chaplains; however, almost all the Cathedrals Group paid chaplains are Christian. Traditional elite universities, with the next highest proportion paid by the university, usually have a Christian (generally Anglican) history, chapels and many years of chaplains being part of their tradition, especially in collegiate universities such as Oxford and Cambridge, so funding of chaplains is often still embedded within these institutions as standard practice. Receiving no payment is the most common option in the red brick, 1960s campus and post-1992 universities, reflecting their more secular foundation; in these universities, chaplaincy was often added later. As Gilliat-Ray (2000: 28) notes, ‘In 1952, there were just eight university chaplains outside Oxford and Cambridge, of which only three were full time. By 1985 most universities, polytechnics and colleges of higher education had some kind of Anglican chaplaincy provision.’ Where chaplains in red bricks, 1960s campus and post-1992 universities are funded, it is usually by religious organisations, who have stepped in to fill the gap.

Differences in faith spaces and religious student societies

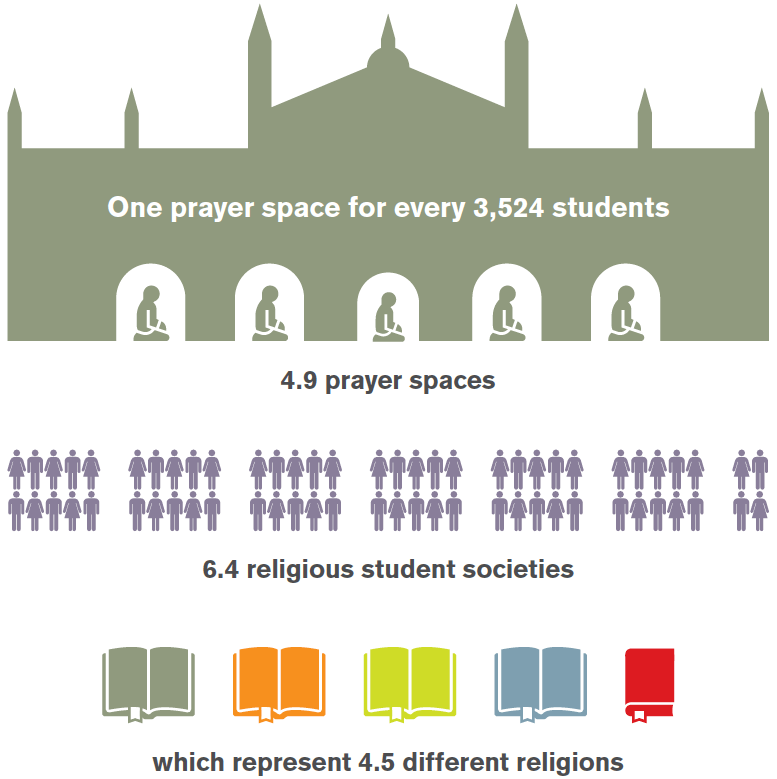

A (mean) average university* has:

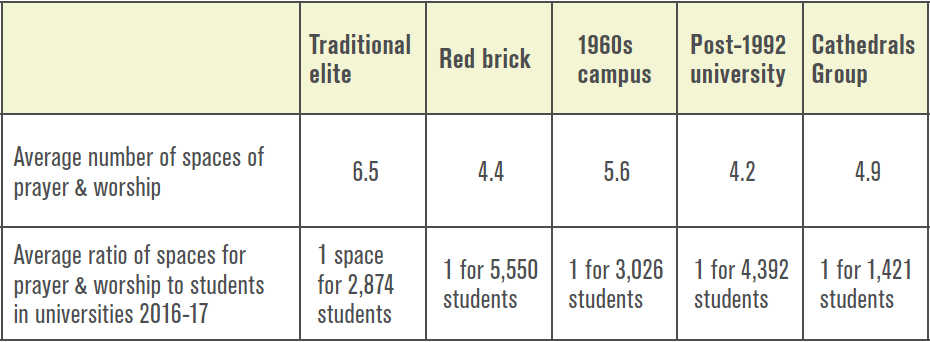

There are differences in the amount of provision at different university types. The most abundant space for prayer and worship for students (calculated using a students-to-spaces ratio) is at Cathedrals Group universities, followed by traditional elites, 1960s campuses, and post-1992 universities, with red bricks having the smallest amount.

A collective act of Christian worship takes place in 81% of universities on a weekly basis, mostly organised by the chaplaincy, with no major differences between types of university. More variation exists for Muslim Friday prayers: these happen in three-quarters of universities, but much less in Cathedrals Group universities (they happen in only 40%, compared to 94% of 1960s campuses, 85% of traditional elites, 76% of post-1992 universities and 71% of red bricks).

Numbers of religion and belief-related student societies is another indicator of the level of religious provision. [See forthcoming study of religious student societies by Simon Perfect and Ben Ryan at Theos

and Kristin Aune.] An average university, according to the ‘lead’ chaplain’s reporting, has 6.4 religious student societies, which represent 4.5 different religions; the number of religions is lower mainly due to large numbers of Christian societies. The numbers of societies for minority religious students was lower than average at Cathedrals Group and post-1992 universities, with few such societies at Cathedrals Group universities.

Cathedrals Group universities may have excellent chaplaincy provision, but with generally poor facilities for prayer or mixing with students of the same minority faith (57% of Cathedrals Group universities do not have a permanent Muslim prayer room, almost double the 30% average of the whole sector [The proportion of universities with at least one permanent Muslim prayer room has risen slightly from 65% ten years ago (Clines 2008: 109) to 70%.]), chaplaincy provision may seem sparse to Cathedrals Group students from non- Christian religions.

Differences in overall resources

Certain types of university resource chaplains better. There are big differences between resources offered by traditional elite and Cathedrals Group universities, who are much more likely to provide pay and resources, and red brick, 1960s campuses and post-1992 universities, who are much less likely to. It might be expected that universities who do not pay chaplains make up for the lack of pay in other ways. But this is not the case apart from, to some extent, in the 1960s campus universities, as Table 7 shows, where ‘more’ and the colour green represents better provision than average and ‘less’ and the colour orange represents worse than average provision.

In the case of physical space for chaplaincy, the mean average number of worship and prayer spaces for chaplaincy at traditional elite universities is 6.5. 1960s campus universities have 5.6, higher than Cathedrals Groups who have 4.9 and red bricks for red bricks who have 4.4. Post-1992 universities provide the smallest amount of dedicated chaplaincy space, an average of 4.2 spaces.

The superior resourcing of traditional elite and Cathedrals Group universities can be explained by their historical connection to the churches and their associated trusts, while the inferior resourcing of the other three groups can be explained by their secular foundation, despite moves towards recognising the newer multi-faith context. Having secular foundations means a variety of things, however, and what it meant historically may not be what it means today. For some universities, secular means ‘religion-free’ or unfriendly to faith, but for some, it means ‘faith-rich’, open to all.

1960s campus universities may be offering superior non-financial resources because of geography: located away from, or at the edges of, towns and cities, there are limited local places of worship or religious resources to point students to, so demand from students has necessitated the creation of bespoke ones on campus. In contrast, red brick universities and post-1992 universities are often located in cities with an existing supply of churches and other religious spaces students can be directed to. The fact that secular-foundation universities have made these adaptions shows that they are attempting to accommodate religious requests.

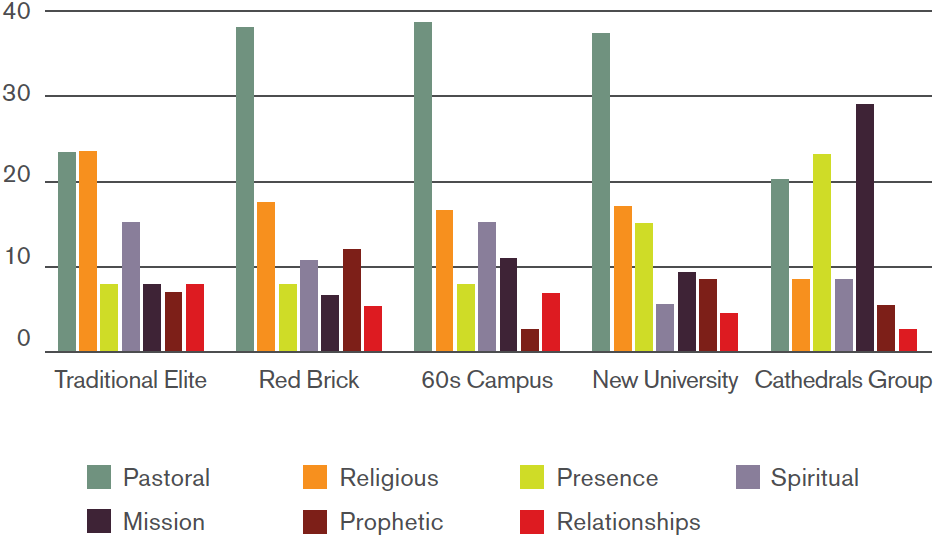

Different perspectives on chaplaincy’s aims

The aims of presence and mission are, distinctively, the aims most commonly articulated by chaplains of Cathedrals Group universities, as Figure 7 shows. Additionally Christian chaplains at Cathedrals Group universities are most likely than at other types of university to use explicitly Christian language when expressing their primary aim.

Differences in how chaplains relate to others in their universities

There are differences in how chaplains relate to others in their universities. Most strikingly, the wider institutional embeddedness of chaplaincy pays significant dividends within the traditional-elite, post-1992 university and Cathedrals Group case studies that are noticeably absent from the red brick and 1960s campus universities. The more avowedly secular foundations of the latter two appear relevant in informing enduring perspectives among staff, but more important are matters of governance and lack of investment. It is also worth noting that the explicitly Christian ethos of the Cathedrals Group university manages to bind staff together in a common project, but this is to some extent frustrated by an overly complex accountability structure which lacks singular leadership. The two lead chaplains at the traditional elite and post-1992 universities appear to thrive in part because they are given autonomy to lead on account of them being trusted by the broader university management. Much can be learned from their example.